***STILL UNDER CONSTRUCTION***

On Thursday, March 28, 1963, nearly six dozen students marched from the segregated, black Main High School to Broad Street in Rome, Georgia’s historic downtown. The students split into small groups and, unsure of what they would encounter, entered four separate drug stores and sat at the tables reserved only for white patrons. In the process, these students instigated one of the city’s largest civil rights protests. The act disrupted the city’s image as a peaceful town with positive race relations, as the white civic and business leaders in Rome preferred to suggest. The Atlanta Constitution described the protest as the city’s “first sign of racial unrest.” In reality, however, it was the product of years of discrimination, tension, and dreams deferred. The Rome Sit-ins are significant as one of the first moments the city confronted its own myths about civil rights and race relations, which had long been suppressed or ignored. The actions of the city’s leaders and police officers indicate that the stories Rome told about itself were not always accurate.

At the time, lunch counters on Broad Street were not the only segregated facilities in Rome. country clubs, swimming pools, and churches were also segregated. The student protestors attended the segregated Main High School, which fell under the jurisdiction of the city school district and accommodated all black students within the county. This despite the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision which went into effect nearly a decade earlier (Anderson, 14, 17). Despite, or perhaps because of, the second-class citizenship afforded to the city’s black population, most white Romans at the time described race relations as one marked by an enforced relationship of “civility.” Black citizens were expected to be quiet and submissive as white Romans carried out “paternalistic racial etiquette” marked by “charity towards blacks, token representation for them in local government, and description of relationships between white employers and their black domestic workers as ‘friendships.’” (Anderson, 22-23). Essentially, many white Romans mistook the forced silence and submissiveness of the city’s black population as indication of positive race relations. Such a complacent, uncomplicated worldview had difficulty accommodating contrary evidence, which made the March 1963 protests a direct challenge to the paternalistic worldview held by the city’s white leadership.

Historical Context

Contrary to the Atlanta Constitution, racial unrest occurred in Rome before March 28, although on a significantly smaller scale. Several attempts to integrate the lunch counters had occurred in the previous months whenever individuals or small groups spontaneously tried to receive service, but due to their size and scale, they never resulted in charges or indicated cracks in Rome’s image of “civility”. The largest protest to that point occurred six weeks before the March sit-ins, when fifteen students attempted to integrate the lunch counters on Broad Street.

Fri, Feb 15, 1963 – 12 · The Atlanta Constitution (Atlanta, Georgia) · Newspapers.com

These protests resulted in the first sit-in-related arrests, but no charges were filed. As a result of these actions, however, city Manager Bruce Hammler warned that any future protests would result in charges. These first sit-ins ultimately did not cause much disruption in the city’s image of civility, but it did raise the stakes for the students who chose to do so. (See: “Negro Leaders Urge Against Demonstration,” Rome News Tribune, Feb 15, 1963, p. 5.)

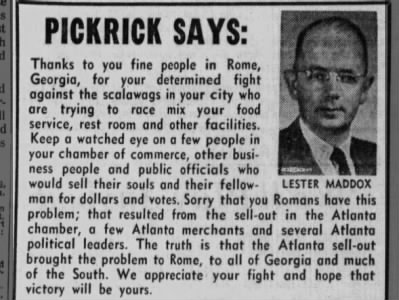

At the beginning of March, Atlanta businessman Lester Maddox congratulated Rome residents for having avoided desegregating their lunch counters and restaurants.

Sat, Mar 9, 1963 – 9 · The Atlanta Constitution (Atlanta, Georgia) · Newspapers.com

Planning the Sit-in

With an atmosphere of protest already strong within the state, Rome only needed a spark before it engaged in protests. Immediate motivation for the sit-in developed a few days before March 29th when Herbert Monford, a Main High Student, attempted to order a drink from a Broad Street soda fountain. The store, of course, denied him service, and closed the lunch counter and splashed him with ammonia when he refused to leave the establishment. Other students attempted to receive service, whether individually or in pairs, but all received the same treatment. (Anderson, 8)

The frustration of these students contrasted with the supposed progress the city assured was happening. Only a year before, a group of black citizens collectively petitioned the “city fathers” over segregation-related grievances, resulting in the partial desegregation of city parks and buses. Additionally, the city library had been integrated a few weeks before the protests. (Parks and buses – Levin, 4; Library, Anderson, 6) The supposed march towards progress had stalled, however. Incrementally integrating Rome public transportation was a massive undertaking, and even then African American patrons still had to sit in the back of the bus. The fact that the lunch counters on Broad Street were still desegregated despite the promises of progress frustrated the young students, who viewed their own actions as a dismissal of the incrementalism favored by the older generation of Rome’s black leaders. (Voices in Protest, 4-5)

The frustration boiled over, and the individual sit-in protesters rallied more numbers to their side. The most visible leader of the student activist group was Lonnie Malone, a Junior at Main High. Malone and the other individual protesters recruited more students throughout the school day, encouraging them to attend a meeting in the Main High School gymnasium after school to plan and prepare for the protest. The majority of the students who attended the protest joined due to this meeting. By the end of the meeting, over one hundred protestors had joined the cause. The exact number is unclear. [Reports often say only sixty-two protested, but that is actually just the number arrested. Arrests only occurred at two of the four locations, meaning potentially over 120 students participated.

![]() Read the transcript or listen to the oral the interview done in 2006-2007 with some of the participants in Rome’s 1963 sit-in. Taking Place: South Rome. Transcript of an oral interview between various members of the black community in South Rome. American Studies Institute, Kennesaw State University, Atlanta, Ga.

Read the transcript or listen to the oral the interview done in 2006-2007 with some of the participants in Rome’s 1963 sit-in. Taking Place: South Rome. Transcript of an oral interview between various members of the black community in South Rome. American Studies Institute, Kennesaw State University, Atlanta, Ga.

Although Malone acted without any outside help from organizations such as the NAACP or the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the planning and preparation for the sit-ins followed the modus operandi of those groups. Malone and other student leaders warned the protestors to expect physical or verbal abuse, and gave strict orders to remain silent throughout the protest unless served. They also checked students for any sharp objects, and dismissed potential protesters who had a record of disciplinary issues. (Voices in Protest, 6)

Finally, the students developed logistics. They planned to target four lunch counters on broad street: Enloe Drugs, located in the 200 block at the corner of Broad Street and Second Avenue (current day Frios), Redford Variety Store, diagonally opposite from Enloe Drugs (current day Spires office), Keith Walgreen, located in the 400 block at the corner of Broad Street and Fifth Avenue and backing up to the Floyd County Courthouse (current day El Zarape), and C.G. Murphy Company, a few buildings down from Keith Walgreen, the central building in the 400 block (current day La Scala). Students divided into twenty groups, with five assigned to each store. The students, anticipating arrests, established a “revolving door protocol.” As soon as police pulled one group out of a store and drove them away in squad cars, the next group would enter. The meeting ended, and the students returned home, intending to carry out their protest the next day. (Voices in protest 6-8; Anderson 8-9)

Arriving on Broad Street

At four in the afternoon on March 29th, 1963, the first group of black students entered the four targeted stores simultaneously. After sitting down, the students pulled out school books and started reading them in silence. (Levin, 11-13) In each of the stores, the managers or other employees immediately approached the students and asked them to leave. In one store, the manager tried to persuade the students that their protests were actually damaging the movement for equality in the city by sabotaging race negotiations. “We almost had it settled about the lunch counters until this happened,” he said. “Now I don’t believe we’ll ever get it settled.” It does not appear that there were any meaningful negotiations in the city at that time to integrate the lunch counters. (Levin, 12).

Despite the requests to leave, the protestors remained silent and continued reading their books. In response, each of the stores closed their lunch counters. The students still refused to move, so the waitresses began to pour water mixed with ammonia on the students in an attempt to “clean” the counters. In one store, after a waitress poured an entire bucket of soapy water and on the protestors, an onlooker encouraged her to “put some ammonia in it, and maybe it will wash the black off them.” Despite the deluge, the students remained silent. (Levin, 14).

Two of the stores simply closed their counters and the protestors waited until the store closed without incident. They did not face charges and were not arrested. At Keith-Walgreen and Redford’s, however, the managers called in the police. In one of the stores, police arrived within minutes of the protest beginning. The officers asked the students to leave and, when they remained silent, officially placed them under arrest. When Lonnie Malone was placed under arrest, he broke his silence and “asked the officer what was the charge. He replied, ‘Loitering.’” (Levin, 25). Once under arrest, the students finally stood and, returning to silence, walked out of the store. Some of the officers grabbed the student’s arms or shoulders and escorted them to the squad cars in front of Keith-Walgreen and Redford’s. As a small act of defiance, the protestors positioned themselves in the car to take as much space as possible. Although the groups of three to five students could have fit inside a single car, their positioning forced the officers to get another one. (Levin, 12)

The protestors expected to be arrested and planned accordingly. As soon as the police car left with the first group of protestors in tow, another group entered the store and sat down. Again, the managers called the police, although there was a wait for the next squad car. This revolving door of protestors and officers continued throughout the afternoon. Small crowds gathered inside the drug stores and on the sidewalk outside. (Levin 12). As more and more people gathered, white members heckled the protestors. They encouraged the waitresses to spill water on them, as above, and hurled insults like a mother with her small daughter who called the protestors “black sons of bitches” and a group of white teenage boys who said “Martin Luther King had better come get his monkeys and carry them back to Africa.” (Levin, 14-15)

At all four locations, the protestors also faced threats from the crowd. At the locations that closed their counters instead of calling the police, the protestors sat for over an hour and a half as crowds gathered and grew more agitated. The students at these stores heard threats like “If we kill about two or three of them, they’ll stop,” and “I would have drowned them if this was my store.” (Levin 16) A group of young white men threatened another protestor by standing behind her and saying “I should pull my knife out and see how brave she really is, see how she can take a stick in her back.” None of the protestors faced serious violence or physical abuse from the crowd or the arresting officers during the sit-ins, but the vitriolic attitudes and hateful comments reveal a great deal about how Rome reacted to those protesting the status quo. (Levin, 14)

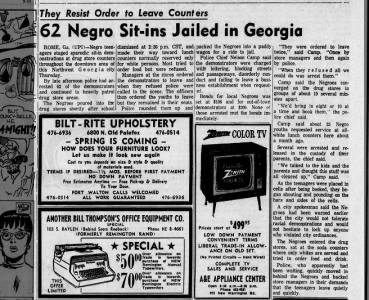

By the end of the protests, police arrested eighteen protesters at Keith Walgreens and forty-four at Redford’s. (“62 Jailed after Rome Sit-ins Demonstration.” Rome News Tribune, March 29, 1963.) Thirty-three of the arrested students were female. Three protestors when asked to leave laid on the floor of the pharmacies and refused to move. Police had to carry them out. (“Trial of Teenage Negro Demonstrators Ended.” Rome News Tribune, 3 April 63) Even as the police arrested the students and took them to the station, the students stayed respectful but defiant. As one student later described her arrest and escort out of the drug store,

“Since I was the last one out, I THANKED the officer who held the door for us. I must say we were riding in style with two chauffeurs. We rode in a 1962 black Ford, engraved in gold, with an inscription, ROME CITY POLICE. The officer at the desk took our belongings and put them away neatly and safely. The officer at the “inn” opened the door to the cell with a large key.” (Levin, 16)

Fri, Mar 29, 1963 – 36 · Pensacola News Journal (Pensacola, Florida) · Newspapers.com

“Let My People Go”: The Protesters in Jail

The police charged the protestors with loitering, disorderly conduct, and failure disperse assemblies following a police order. An unintended consequence of holding the protests on a Friday[?] afternoon was that the students had to wait until the following Monday to appear in court. Bond was posted at one-hundred and two dollars per student. Very few students or their families paid it, so most of them stayed in jail over the weekend. (Anderson, 9)

While in jail, the students remained defiant, but were no longer silent. Although the students were held across more than four different cells, each cell was able to talk with the others. The students quickly began to sing to one another spirituals, modern songs, and the “Negro National Anthem:” “Life Every Voice and Sing.” One of the songs was a deviation of “Go Down Moses”: “Go down Kennedy, Way down in Georgia Land, Go tell the police chief, let my people go.”(Levin, 20)

This defiance persisted despite the horrendous conditions the police forced them into. Each cell had at least fifteen students, with one having over seventeen. All but one of the cells only had four beds, and in one of the cells a drunk woman thrown in jail earlier that day was already occupying one of them. The students referred to this woman as “El Zoro,” and didn’t want to sit next to her because she was “nasty.” Most of the male protestors were held in the “drunk tank,” a steel and concrete cell with “no light, no ventilation, and worst of all, no beds.” Lonnie Malone was housed in this cell, and described it as a “man-made hell.” When the girls asked “El Zoro” about the drunk cell, she just called it “nothing but a shithole.” (Levin 18-20)

In addition to the overcrowded cells themselves, the guards at the jail made the experience as uncomfortable as possible. During the day, the guards locked the windows shut and turned on the heat, but during the spring nights they opened the windows and blasted the air conditioning. (Levin 21). The guards also prevented any outside visitors into the jail, and blocked the students’ families from bringing in outside food. The students wished that was not the case, of course, especially because the food was atrocious. Dinner the first night was “dried beans, sauerkraut, and dried hard cornbread.” Even though the protestors hadn’t eaten anything since lunch, they threw their dinner out into the hallway in frustration, along with the filthy, unwashed sheets the guards gave them to sleep with. (Levin, 20). White news outlets were happy to report this delinquent behavior, and coupled it with accusations that the students spat on the arresting officers. (Atlanta Constitution, March 30th, 1963).

Sat, Mar 30, 1963 – 1 · The Atlanta Constitution (Atlanta, Georgia) · Newspapers.com

Sat, Mar 30, 1963 – 11 · The Atlanta Constitution (Atlanta, Georgia) · Newspapers.com

Throughout the weekend, the guards grew more lenient, allowing the protestors to take showers and providing better meals. By Sunday, sutside visitors could enter and bring a change of clothes to the students. Some of the parents smuggled in food for the protesters by wrapping it in the new clothing. A few of the students held in the drunk tank were transferred to another cell with proper bunks. More and more of the students’ parents were posting bond. (Levin, 23-24)

The noise and spectacle of the students in jail attracted onlookers who gathered outside the windows and looked through. Some white students gathered at the adjacent library and danced to the singing of the jailed protests appropriately enough by doing “the twist,” a dance popularized by black performers but appropriated by white dancers. Friends and families came to the jail windows, but police quickly forced away all but the white onlookers. Nevertheless, Through the windows of the jail, the students could see some of their classmates walking into downtown. They learned from passersby that some students continued the protests in solidarity. The second day of protests resulted in no arrests, likely because of both the smaller number of demonstrators and the jail’s inability to hold additional prisoners. (Levin, 21, 24)

On Sunday morning, the students held a makeshift church service. Two ministers were allowed to come in and distribute religious pamphlets, while another student, Ervin, led the group in hymns, prayer, and a sermon comparing their struggle to that of Moses and the Israelites in Egypt. The guards finally allowed outside food, and the Metropolitan Methodist Church and many of the the students’ mothers brought in dinner “which was the best we had since coming to jail.” After four long days in jail, the students tried to look as presentable as possible for their appearance in court the next day. (Levin, 27)

Recorder Court

To represent the students, the state office of the NAACP sent lawyers to represent the students in the trial. Vernon Jordan and Horace T. Ward, the same lawyers who had sued to integrate the University of Georgia two years earlier, arrived on Saturday and spoke to the students. They negotiated with the court to try the students in groups of three and four, with one spokesperson selected to speak for each. On Monday, the students appeared before Recorder Court Judge Tenry Fulbright. The students hoped to be released from jail that day, but when court adjourned Monday afternoon not all the groups had appeared before the judge, so all the protestors were kept an extra day on bond. (Atlanta Constitution, April 2 1963; Levin 29).

The lawyers challenged the fairness of the law, calling the drug store managers as witness and asking “Why a store that was open to the public for its service would not permit a person to eat at the counter because he or she is a Negro.” The lawyers also countered misinformation spread by the managers, such as rumors that the students did not bring money to the protests and, rather than a good-faith effort to receive service, were actually deliberately causing discontent. In reality, every student had at least enough money to buy a small drink, and the lawyers used this strategy to question the credibility of the managers. Throughout the trial, the students remained defiant. When the judge asked one of the protestors whether they would sit-in again if found not guilty, he responded “Yes sir, I would be glad to sit-in for my rights.” (Levin 28-30).

Tue, Apr 2, 1963 – 8 · Chattanooga Daily Times (Chattanooga, Tennessee) · Newspapers.com

Despite the best efforts of the NAACP lawyers, the students were still found guilty. Fifty-seven of the sixty-two protestors were convicted of violating city ordinances regarding disorderly conduct. Five of the protesters were not convicted because they were fourteen, and the judge determined they did not “realize the seriousness of their actions.” The vast majority of the fifty-seven students were given the option of serving five days of jail as punishment or pay a fine of fifty dollars. The two girls were given only three days or twenty-five dollars because, when they were escorted out of the pharmacy five days earlier, they thanked the officers for holding the doors open. On the other hand, the three protestors who lad on the floor and forced the police to carry them out received stricter punishments of ten days in jail or a hundred dollar fine. Most students elected to serve the time in jail, but Howard and Jordan negotiated for the students to have the option to serve it on consecutive weekends rather than the next few days so they would not have to miss school. Defiant to the end, most of the students chose to serve it straight through, although those serving on weekends had the punishment lifted after only two weekends. (Levin)

Wed, Apr 3, 1963 – 4 · Chattanooga Daily Times (Chattanooga, Tennessee) · Newspapers.com