- 1877 – The Georgia State Constitution requires tax-payer-funded schools to educate black and white children in separate facilities.

- 1953 – Georgia legislature passes an appropriations bill that refuses to provide funding to any integrated public schools.

- 1954 – The Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education orders schools to desegregate “with all deliberate speed.” Vague wording allows many Southern schools to delay school integration.

- Georgia citizens ratify a constitutional amendment allowing for publicly-funded education grants to pay for private education. Most Floyd County voters oppose the measure.

- 1955 – The Georgia Legislature made it a felony punishable by two years in prison for anyone to spend state money to fund an integrated school.

- 1956 – The Georgia State Legislature passes several pieces of legislation to uphold segregation in the education system. These include:

- 1959 – Atlanta Public Schools receive a court order to desegregate.

- 1960 – The Georgia State Legislature creates the General Assembly Committee on Schools to hold hearings around the state to determine whether the citizens of Georgia prefer to close down the public schools ordered to integrate and provide grants to residents to attend private schools or whether they want to keep public schools open even if they were desegregated.

- John Sibley, an Atlanta businessman and Berry College trustee, is appointed to chair the General Assembly Committee on Schools. It becomes known as the Sibley Commission.

- The Sibley Commission hearing for North Georgia occurs in Cartersville, GA on 11 March 1960. Some of the Floyd Country residents who spoke include:

- E. Russell Moulton, superintendent of the Lindale schools, said that the Floyd County Education Association favored keeping the public schools open;

- E.K. Grass representing the Rome Central Labor Union’s members stated that the Union’s members favored closing down the schools to preserve segregation;

- Dr. Randall H. Minor, President of Shorter College, spoke for the Rome Chamber of Commerce and said the majority of the Chamber’s directors wanted to keep the schools open and allow local communities to determine how the schools would operate;

- Dr. Robert Norton, chairman of the Rome Board of Education, said that the Rome Educational Association wanted to keep the schools open;

- Mrs. George Polston, who represented the Rome League of Women Voters, said the League favored closing the public schools and using vouchers for private school attendance;

- Leon V. Gresham spoke for the Shanklin-Attaway Post of the American Legion whose members favored maintaining segregated schools;

- Jule Levin, a Rome merchant, wanted to keep the public schools open and allow local communities to manage the schools;

- Rev. A. M. Von Almen, pastor of the Rome First Christian Church, spoke on behalf of the Rome Christian Council which favored keeping the schools open;

- W.T. Levins, the executive secretary of Floyd Community Services, spoke in favor of keeping the schools open; and

- Rev. Harold McDaniel, the chaplain of the Berry Schools, favored keeping the schools open and letting local communities decide how to deal with the issue of school integration.

- The Sibley Commission held ten hearings throughout Georgia and discovered that 60% of the state was willing to close all public schools to avoid desegregation. Fearing the economic consequences of such a move, the Commission recommends adopting a “local option” approach. This would prevent the state from automatically closing schools ordered to integrate and allow local communities to decide how to deal with school desegregation.

- 1961 – Georgia Governor Ernest Vandiver announces that the General Assembly will introduce three new educational bills and an amendment to the state constitution that would allow individual communities, rather than the state, to decide whether or not to close down schools ordered to desegregate by the courts. This approach, he claims in a January 18, 1961, speech would allow Georgia to use “Every legal means and every legal resource at our command to maintain separate education….” The state’s educational reforms created a slow, piecemeal system where only some school districts desegregated while most did not. By 1962, nearly 200 school districts across Georgia are still segregated, including the Rome City Schools.

- 1964 – The Civil Rights Act is passed, empowering the U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare to force schools to desegregate by withholding federal funding.

- A few days after the Civil Rights Act was passed, the Rome NAACP petitioned Rome City Schools to desegregate. The chairman of the RCS School Board stated that the board “did not have any plans to integrate” and that “like all Southern people, my preference would be segregated schools.”

- 1965 – Rome and Floyd County Schools learned that they faced the loss of $140,000 in federal aid if they chose to maintain racial segregation.

- Rome City School System announced plans to Institute a “Freedom of Choice” desegregation plan, which allowed students to request the specific school in the system they wanted to attend. The Rome superintendent then decided based on available space, student qualifications, and student residence whether or not the placement would be allowed. Initially, only grades 1-3 were eligible to participate in the plan during the 1965-1966 school year.

- The U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare requires some junior and senior high grades also be desegregated during the 1965-1966 school year and that all grades be integrated by 1967-1968. In response, Rome announced that it would also offer the Freedom of Choice plan to students in grades 7, 9, and 12 beginning in the fall of 1965.

- 59 African American students request to attend formerly white schools. No white students request to attend formerly black schools.

- 1966 – All grades in the Rome City School System are open for integration.

- 484 African American students in Rome attend formerly all-white schools. This included:

- West Rome High School: 60 black students

- East Rome High School: 85 black students

- East Rome Junior High: 83 black students

- Central Primary: 36 black students

- North Rome: 7 black students

- Northside: 13 black students

- Fourth Ward: 31 black students

- Elm Street: 28 black students

- South Rome: 41 black students

- Eighth Ward: 29 black students

- East Rome Elementary: 74 black students

- West End: 0 black students

- 484 African American students in Rome attend formerly all-white schools. This included:

- 1967 – A ruling by the U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare requires all school systems using Freedom of Choice desegregation plans to show that they had substantially eliminated racially identifiable schools. Since Rome still had five schools attended by only African American students (Main High and Elementary, Reservoir, Mary T. Banks, and Anna K Davie), this ruling required a complete reorganization of the Rome City School System’s desegregation plan.

- 1968 –Rome City Schools proposed a desegregation plan that would close Main High School, Graham Street Elementary, and begin the process of closing Mary T. Banks Elementary School.

- The editorial page of the Rome News Tribune referred to the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare’s push to move the system beyond the “Freedom of Choice” desegregation plan as “The systematic rape of the Rome public schools….”

- Supreme Court ruled that Freedom of Choice desegregation plans are ineffective at adequately integrating school systems.

- Rome School Board makes a specific proposal for the 1968-69 school year to expand desegregation including more faculty integration. Some of these changes included:

- Main High School – add 4 white teachers

- East Rome High School – add 6 black teachers

- West Rome High School – add 6 black teachers

- East Rome Junior High School – add 3 black teachers

- Elm Street Elementary – add 2 black teachers

- Fourth Ward School – add 1 and 1/2 black teachers

- Eighth Ward Elementary School – 2 black teachers

- Mary T. Banks Elementary – add 2 white teachers

- Anna K. Davie – add 3 white teachers

- North Rome-Northside Elementary – add 2 black teachers

- Central Primary Elementary – add 1 and 1/2 black teachers

- East Rome Elementary – add 1 and 1/2 black teachers

- Main-Reservoir Elementary – add 3 white teachers

- West End Elementary – add 1 and 1/2 black teachers

- South Rome – add 1/2 black teachers

- Rome News-Tribune publishes the May 21, 1968 letter from the Department of Housing, Education, and Welfare regarding Rome school integration and the Rome Board of Education’s June 6, 1968 response.

- Rome Council on Human Relations proposed to the Rome City Board of Education to keep Main High School open.

- 1969 – The Department of Housing, Education, and Welfare approved Rome’s 1969-1970 desegregation plan.

- Rome was one of 83 Georgia School Districts sued by the U.S. Justice Department for failure to desegregate quickly enough.

- 2008 – Desegregation court order lifted from the Rome City School System.

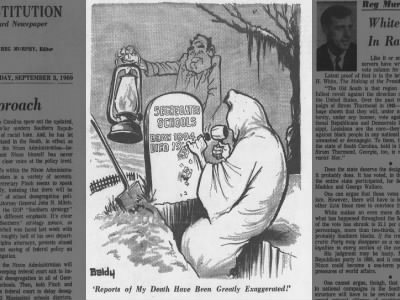

Political Cartoon about School Desegregation

Wed, Sep 3, 1969 – 4 · The Atlanta Constitution (Atlanta, Georgia) · Newspapers.com

Last updated: 5 May 2024